If you are reading this blog post via a 3rd party source it is very likely that many parts of it will not render correctly (usually, the interactive graphs). Please view the post on dogesec.com for the full interactive viewing experience.

tl;dr

STIX 2.1 allows you to tell stories by connecting objects together to form the story-line of cyber actors, campaigns, incidents, and much more. In this post I explain how.

Examples of what is possible

Overview

The full STIX 2.1 specification makes for a lot of reading.

Yes, there’s A LOT to it. I will try my best to simplify it.

STIX 2.1 revolves around Objects. There are five Core Object types in STIX 2.1:

- STIX Domain Objects (SDOs)

- STIX Cyber-observable Objects (SCOs)

- STIX Meta Objects (SMOs)

- STIX Relationship Objects (SROs)

- STIX Bundle Objects (SBOs)

Lets break each one of these out to explain more…

STIX Domain Objects (SDOs)

Most widely known are the predefined STIX Domain Objects (SDOs) used to represent more abstract concepts commonly used in cyber threat intelligence.

To begin with it is generally best to think of these objects as being more descriptive; the description of a threat actor, or perhaps how a piece of malware works, the TTPs employed.

Here’s a list of the STIX 2.1 SDOs…

- Attack Pattern

- A type of TTP that describes ways that adversaries attempt to compromise targets.

- Campaign

- A grouping of adversarial behaviors that describes a set of malicious activities or attacks that occur over a period of time against a specific set of targets.

- Course of Action

- A recommendation from a producer of intelligence to a consumer on the actions that they might take in response to that intelligence.

- Grouping

- Explicitly asserts that the referenced STIX Objects have a shared context, unlike a STIX 2.1 Bundle (which explicitly conveys no context).

- Identity

- Actual individuals, organisations, or groups as well as classes of individuals, organizations, systems or groups (e.g., the finance sector) that are non-malicious. Use the Threat Actor SDO for those operating with malicious intent.

- Incident

- Covers a security incident that has occured

- Indicator

- Contains a pattern that can be used to detect suspicious or malicious cyber activity.

- Infrastructure

- Represents a type of TTP and describes any systems, software services and any associated physical or virtual resources intended to support some purpose (e.g., C2 servers used as part of an attack, device or server that are part of defence, database servers targeted by an attack, etc.).

- Intrusion Set

- A grouped set of adversarial behaviors and resources with common properties that is believed to be orchestrated by a single organization.

- Location

- Represents a geographic location.

- Malware

- A type of TTP that represents malicious code.

- Malware Analysis

- The metadata and results of a particular static or dynamic analysis performed on a malware instance or family.

- Note

- Conveys informative text to provide further context and/or to provide additional analysis not contained in the STIX Objects, Marking Definition objects, or Language Content objects which the Note relates to.

- Observed Data

- Conveys information about cyber security related entities such as files, systems, and networks using the STIX Cyber-observable Objects (SCOs).

- Opinion

- An assessment of the correctness of the information in a STIX Object produced by a different entity.

- Report

- Collections of threat intelligence focused on one or more topics, such as a description of a threat actor, malware, or attack technique, including context and related details.

- Threat Actor

- Actual individuals, groups, or organizations believed to be operating with malicious intent.

- Tool

- Legitimate software that can be used by threat actors to perform attacks or by teams to defend against attacks.

- Vulnerability

- A mistake in software that can be directly used by a hacker to gain access to a system or network (commonly an official CVE, but can be any vulnerability).

All STIX objects have pre-defined properties that make up the object. These are defined in the specification.

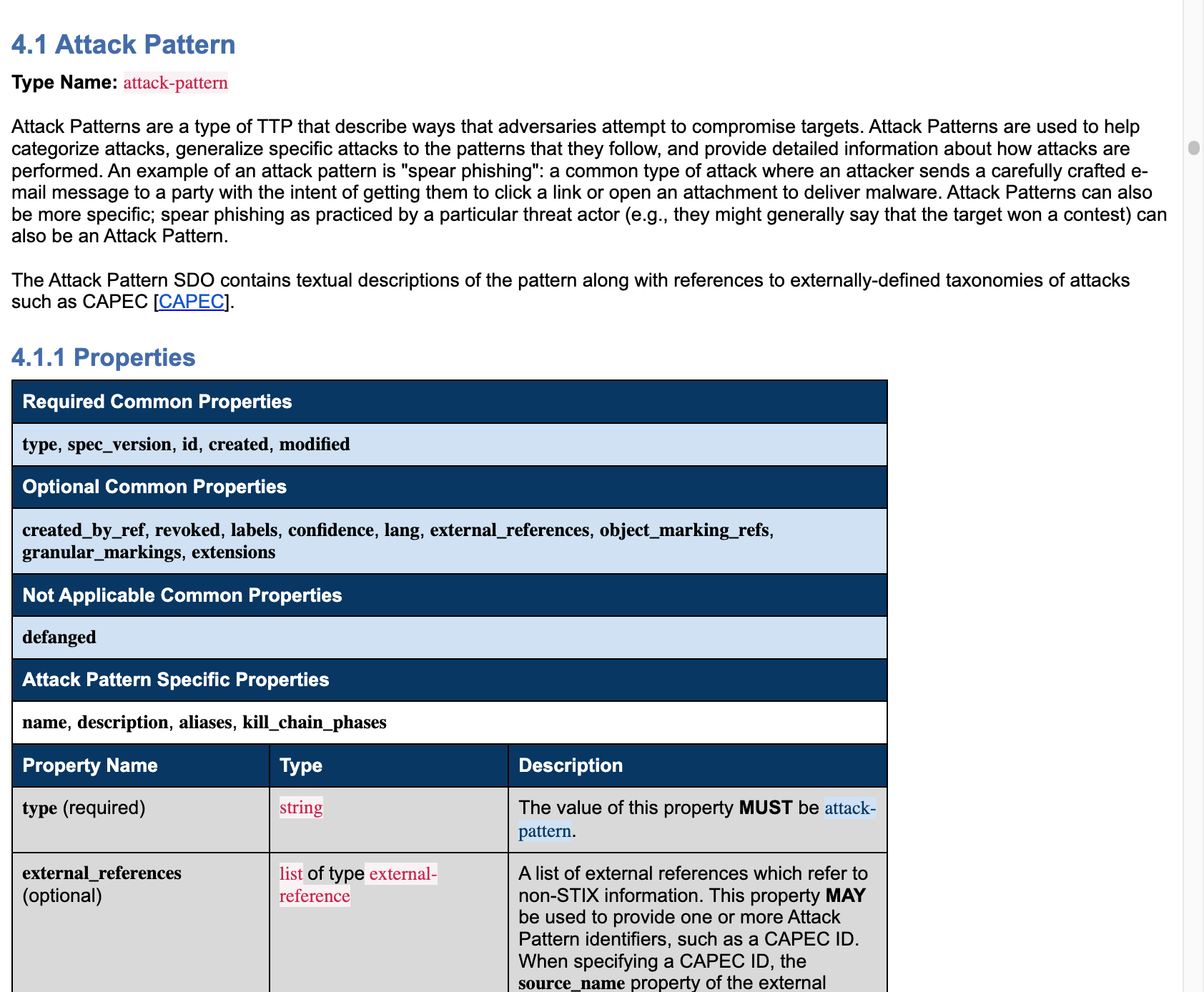

Here you can see them for the Attack Pattern object;

Common properties are properties found in more than one object. This applies to all STIX 2.1 Object types (SDO, SCO, SMO, SRO).

For example, all objects have an id property.

Some properties are required, some of are optional, and some do not apply (that is, cannot be used).

To demonstrate, if I was creating an Attack Pattern object I would NEED to assign it the following common properties; type, spec_version, id, created, modified.

Optionally, I could also use the properties; created_by_ref, revoked, labels, confidence, lang, external_references, object_marking_refs, granular_markings, extensions.

Objects also have their own specific properties. In a similar way to common properties, some of these are required, others are optional

In the case of an Attack Pattern these are name (required), description (optional), aliases (optional), kill_chain_phases (optional).

STIX 2.1 Objects are written in JSON.

Here you can see the properties listed as keys, with the specific values for each filled in, for an Attack Pattern object;

{

"type": "attack-pattern",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "attack-pattern--0c7b5b88-8ff7-4a4d-aa9d-feb398cd0061",

"created": "2016-05-12T08:17:27.000Z",

"modified": "2016-05-12T08:17:27.000Z",

"name": "Spear Phishing",

}

The values that can be used for each property are defined in the specification.

Using Attack Pattern as an example, the type property must always equal attack-pattern, the name can be any string of text.

If I add the kill_chain_phases Attack Pattern specific property to the object, the value must be a list of type kill-chain-phase. The Kill Chain Phase data type is described here.

Here you can see the data types looks as follows;

"kill_chain_phases": [

{

"kill_chain_name": "<STING>",

"phase_name": "<STRING>"

}

]

Adding this to the Attack Pattern object I get something that could look as follows;

{

"type": "attack-pattern",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "attack-pattern--0c7b5b88-8ff7-4a4d-aa9d-feb398cd0061",

"created": "2016-05-12T08:17:27.000Z",

"modified": "2016-05-12T08:17:27.000Z",

"name": "Spear Phishing",

"kill_chain_phases": [

{

"kill_chain_name": "lockheed-martin-cyber-kill-chain",

"phase_name": "reconnaissance"

}

]

}

STIX Cyber-observable Objects (SCOs)

STIX Cyber-observable Objects (SCOs) are very similar to SCOs in their structure, however, whilst I said earlier SDOs were more descriptive representation of threat intelligence concepts, SCOs are atomic values.

For many already in the world of threat intelligence, SCOs are commonly referred to as IOCs. They are evidential bits of information. IPs, domains, file hashes… things that do not change.

This is why using SDOs and SCOs together is useful.

For example, you could have two SCOs representing an MD5 hash value and a URL, that both have a relationship to a Malware SDO. The SCOs are evidential bits of information describing how the Malware is operating.

By associating SCOs with SDOs it is possible to convey a higher-level understanding of the threat landscape, and to potentially provide insight as to the who and the why.

Here is a full list of predefined STIX 2.1 SCOs available for use:

- Artifact Object

- The Artifact object permits capturing an array of bytes (8-bits), as a base64-encoded string, or linking to a file-like payload.

- AS Object

- The AS object represents the properties of an Autonomous System (AS).

- Directory Object

- The Directory object represents the properties common to a file system directory.

- Domain Name Object

- The Domain Name object represents the properties of a network domain name.

- Email Address Object

- The Email Address object represents a single email address.

- Email Message Object

- The Email Message object represents an instance of an email message, corresponding to the internet message format described in RFC5322 and related RFCs.

- File Object

- The File object represents the properties of a file.

- IPv4 Address Object

- The IPv4 Address object represents one or more IPv4 addresses expressed using CIDR notation.

- IPv6 Address Object

- The IPv6 Address object represents one or more IPv6 addresses expressed using CIDR notation.

- MAC Address Object

- The MAC Address object represents a single Media Access Control (MAC) address.

- Mutex Object

- The Mutex object represents the properties of a mutual exclusion (mutex) object.

- Network Traffic Object

- The Network Traffic object represents arbitrary network traffic that originates from a source and is addressed to a destination.

- Process Object

- The Process object represents common properties of an instance of a computer program as executed on an operating system.

- Software Object

- The Software object represents high-level properties associated with software, including software products.

- URL Object

- The URL object represents the properties of a uniform resource locator (URL).

- User Account Object

- The User Account object represents an instance of any type of user account, including but not limited to operating system, device, messaging service, and social media platform accounts.

- Windows Registry Key Object

- The Registry Key object represents the properties of a Windows registry key.

- X.509 Certificate Object

- The X.509 Certificate object represents the properties of an X.509 certificate, as defined by ITU recommendation X.509.

Like SDOs, SCOs have common and some unique properties, some of which are required and some of which are optional.

Here’s an example for IPV4 addresses;

If I were to create an IPv4 SCO, I would need to include the properties; type (common), id (common), and value (object specific).

For example, this IPv4 SCO includes only the required properties;

{

"type": "ipv4-addr",

"id": "ipv4-addr--ff26c055-6336-5bc5-b98d-13d6226742dd",

"value": "198.51.100.3"

}

You’ll also notice I can use the optional properties resolves_to_refs and belongs_to_refs in an IPv4 SCO, among other optional properties.

Here, I can start to create relationships between objects that are related.

Looking at the specification for the resolves_to_refs property;

Specifies a list of references to one or more Layer 2 Media Access Control (MAC) addresses that the IPv4 address resolves to. The objects referenced in this list MUST be of type

mac-addr.

So in this property I can point the IPv4 SCO to a MAC Address SCO to describe where the IPv4 resolves to.

The IPv4 address might look as follows;

{

"type": "ipv4-addr",

"id": "ipv4-addr--ff26c055-6336-5bc5-b98d-13d6226742dd",

"value": "198.51.100.3",

"resolves_to_refs": "mac-addr--65cfcf98-8a6e-5a1b-8f61-379ac4f92d00"

}

And the referenced MAC Address SCO

{

"type": "mac-addr",

"id": "mac-addr--65cfcf98-8a6e-5a1b-8f61-379ac4f92d00",

"value": "d2:fb:49:24:37:18"

}

It is important to note here, this is not a pure STIX Relationship, defined using an SRO. They are embedded relationships. Embedded relationships are listed inside _refs and _ref properties of an object. SROs are standalone objects to denote a relationship between two objects. More about that to follow later in the post.

The observant among you will have noticed that the specification also includes ID Contributing Properties for SCOs (these only exist for SCOs). This comes down to the id generation of the object.

Ultimately this means the same SCO for an atomic object, e.g. 1.1.1.1, will always have the same id no matter who created it. I won’t go into that here, but this part of the STIX specification will explain all.

STIX Meta Objects (SMOs)

Whereas SDOs and SCOs provided direct information about a particular CTI concept, STIX Meta Objects can be though of metadata for other STIX objects.

There are three types of SMO;

- Language Content

- Allow for conversion of STIX SDOs, SCOs, or SROs to other languages.

- Data Markings

- Represent restrictions, permissions, and other guidance for how data can be used and shared.

- Extension Definition

- Define how to create custom STIX objects, or define custom properties for existing objects. This will be covered in detail in later material.

Language Content

Language content is content SMOs are used to translate the content of an SDO, SCO, or SRO.

For example, lets imagine I have a Campaign object;

{

"type": "campaign",

"id": "campaign--12a111f0-b824-4baf-a224-83b80237a094",

"lang": "en",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"created": "2017-02-08T21:31:22.007Z",

"modified": "2017-02-08T21:31:22.007Z",

"name": "Bank Attack",

"description": "More information about bank attack"

}

Note the use of the lang common property in the Campaign SDO.

Looking at the specification for the lang property;

The lang property identifies the language of the text content in this object. When present, it MUST be a language code conformant to [RFC5646]. If the property is not present, then the language of the content is en (English). This property SHOULD be present if the object type contains translatable text properties (e.g. name, description).

Thus, I know this object is written in English.

Should I want to translate the original object word-for-word, I would not make another Campaign Object. Instead I would use a Language Content object.

For example here I provide an German and French translation of the name and description properties from the original Campaign Object (referenced below using the object_ref property);

{

"type": "language-content",

"id": "language-content--b86bd89f-98bb-4fa9-8cb2-9ad421da981d",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"created": "2017-02-08T21:31:22.007Z",

"modified": "2017-02-08T21:31:22.007Z",

"object_ref": "campaign--12a111f0-b824-4baf-a224-83b80237a094",

"object_modified": "2017-02-08T21:31:22.007Z",

"contents": {

"de": {

"name": "Bank Angriff",

"description": "Weitere Informationen über Banküberfall"

},

"fr": {

"name": "Attaque Bank",

"description": "Plus d'informations sur la crise bancaire"

}

}

}

Data Markings

Data Markings represent restrictions, permissions, and other guidance for how data can be used and shared.

This information is conveyed in Marking Definition objects.

Marking Definition

If I want to display a custom statement to apply to an object, I can use the definition.statement property in a Marking Definition object.

For example, I use Marking Definition objects to convey which one of our tools generated the object…

{

"type": "marking-definition",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "marking-definition--54ea22fe-d360-4804-92c4-6b370be260b5",

"created_by_ref": "identity--d2916708-57b9-5636-8689-62f049e9f727",

"created": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"definition_type": "statement",

"definition": {

"statement": "This object has no copyright. It's just for a demo"

}

}

Note the use of definition_type = statement

The STIX 2.1 specification also contains four predefined Marking Definition related to TLPs. Here is the one for TLP:White…

{

"type": "marking-definition",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "marking-definition--613f2e26-407d-48c7-9eca-b8e91df99dc9",

"created": "2017-01-20T00:00:00.000Z",

"definition_type": "tlp",

"name": "TLP:WHITE",

"definition": {

"tlp": "white"

}

}

Here the definition_type = tlp. You cannot use this definition_type yourself as it is a reserved property.

Other instances of tlp-marking MUST NOT be used or created (the only instances of TLP marking definitions permitted are those defined here).

So lets say I wanted to “mark” my Campaign object with the two Marking Definition Objects to denote it has no copyright and is TLP:White.

To do this I would use the common property, object_marking_refs as follows;

{

"type": "campaign",

"id": "campaign--12a111f0-b824-4baf-a224-83b80237a094",

"lang": "en",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"created": "2017-02-08T21:31:22.007Z",

"modified": "2017-02-08T21:31:22.007Z",

"name": "Bank Attack",

"description": "More information about bank attack",

"object_marking_refs": [

"marking-definition--54ea22fe-d360-4804-92c4-6b370be260b5",

"marking-definition--613f2e26-407d-48c7-9eca-b8e91df99dc9"

]

}

Whereas object markings (object_marking_refs) apply to an entire STIX Object or Marking Definition and all its properties, granular markings allow both markings to be applied to individual portions of STIX Objects.

Following on from the Campaign example, lets imagine the description property contained sensitive information and needed to be marked as TLP:Red.

I could do this using Granular Marking by defining the Marking Definition and selectors (the properties it applies to) as follows;

{

"type": "campaign",

"id": "campaign--12a111f0-b824-4baf-a224-83b80237a094",

"lang": "en",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"created": "2017-02-08T21:31:22.007Z",

"modified": "2017-02-08T21:31:22.007Z",

"name": "Bank Attack",

"description": "More information about bank attack",

"object_marking_refs": [

"marking-definition--54ea22fe-d360-4804-92c4-6b370be260b5",

"marking-definition--613f2e26-407d-48c7-9eca-b8e91df99dc9"

],

"granular_markings": [

{

"marking_ref": "marking-definition--5e57c739-391a-4eb3-b6be-7d15ca92d5ed",

"selectors": [

"description"

]

}

]

}

STIX Relationship Objects (SROs)

So far in this post I have covered how SDOs, SCOs and SMOs have relationships and how that can be defined in common or object specific _ref or _refs properties.

STIX Relationship Objects are similar, but offer a much richer way to represent and describe certain types of relationships between STIX Objects.

An SRO defines and describes relationships between two STIX SDOs or a STIX SCO and SDO.

There are actually two types of SROs:

- Relationship (

"type": "relationship")- This Relationship Object is the most commonly used to define and describe links between STIX 2.1 Objects

- Sighting (

"type": "sighting")- A Sighting denotes the belief that something in CTI (e.g., an indicator, malware, tool, threat actor, etc.) was seen. Sightings are used to track who and what are being targeted, how attacks are carried out, and to track trends in attack behavior.

As Relationships are the most used type, lets cover them first.

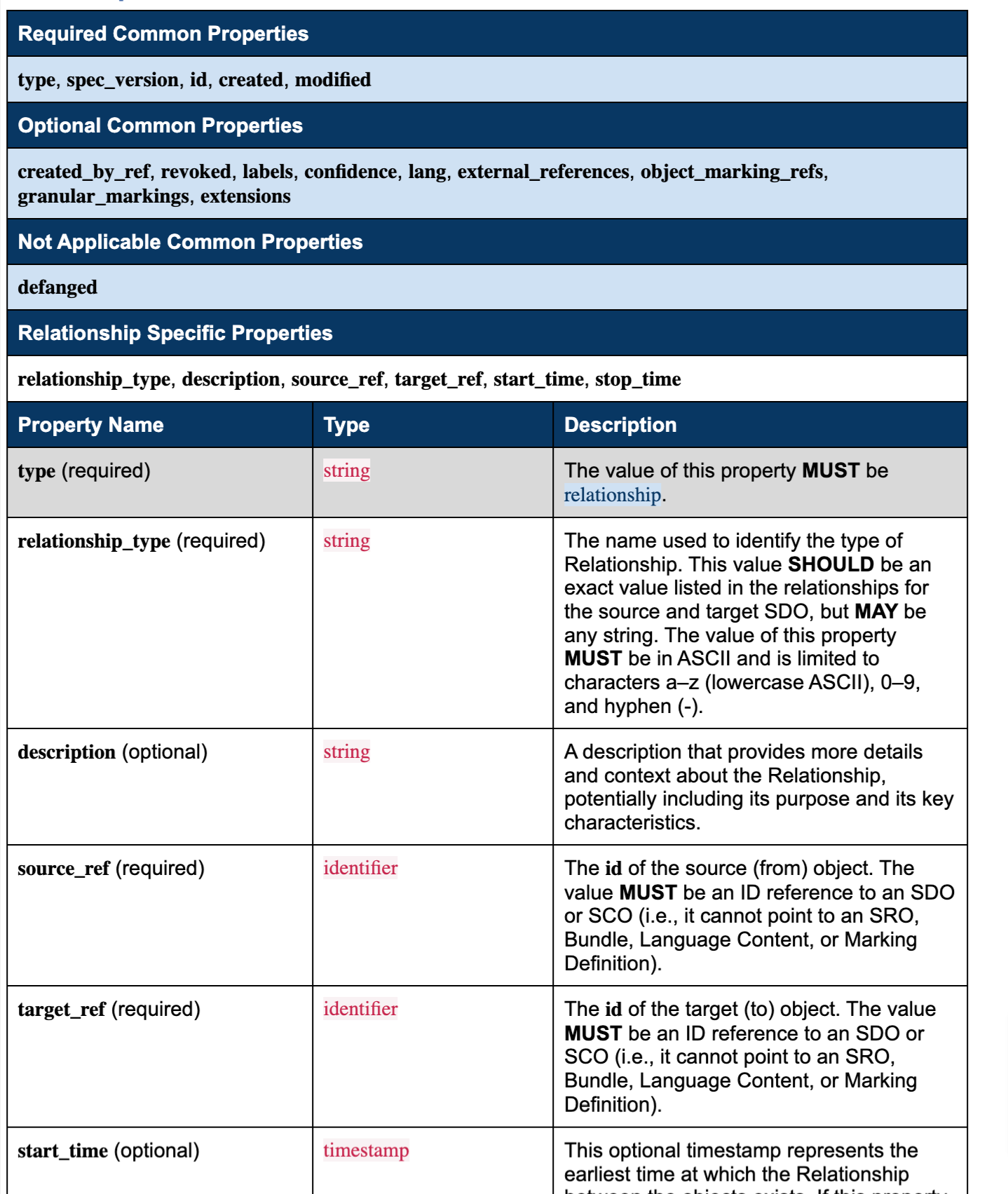

Relationship SROs

Relationship objects are very similar to SDOs and SCOs in that they have required and optional Properties, however, they have three very important Relationship object specific required properties;

relationship_description: a description of the relationship between two objects.source_ref: the source object of the relationshiptarget_ref: the target object of the relationship

Lets look at an example relationship;

{

"type": "relationship",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "relationship--6598bf44-1c10-4218-af9f-75b5b71c23a7",

"created": "2015-05-15T09:12:16.432Z",

"modified": "2015-05-15T09:12:16.432Z",

"relationship_type": "uses",

"source_ref": "threat-actor--6d179234-61fc-40c4-ae86-3d53308d8e65",

"target_ref": "malware--2485b844-4efe-4343-84c8-eb33312dd56f"

}

Here a Threat Actor SDO is linked to a Malware SDO to describe that the Threat Actor is using "relationship_type": "uses" the referenced Malware.

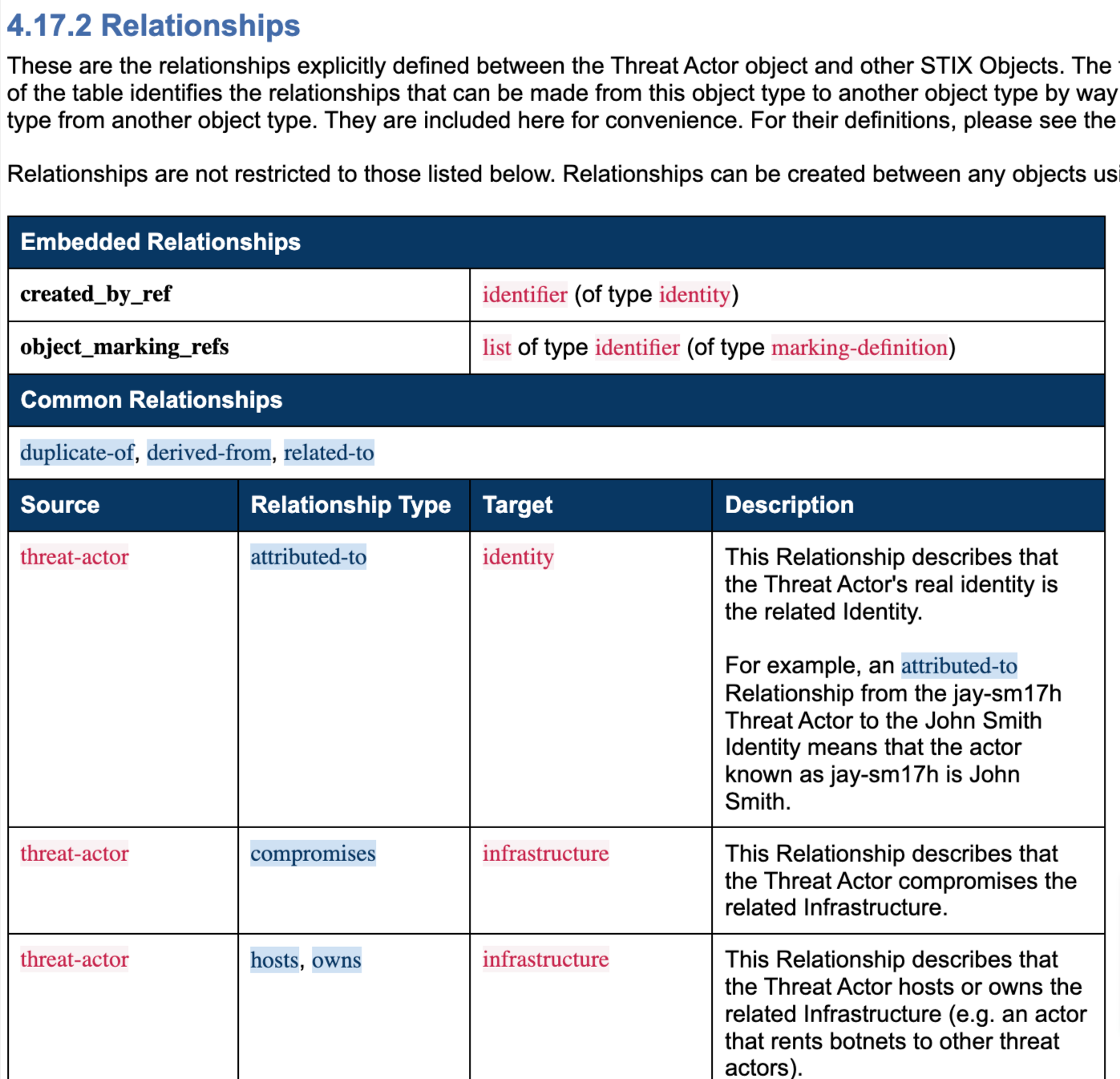

The STIX specification lists common and object specific relationships for each object.

For example, a Threat Actor SDO (source_ref) is attributed-to and Identity SDO (target_ref) is an object specific relationship for a Threat Actor.

The reason for common relationships and descriptions is to try and get creators to use common terminology. Instead of creating relationship_type being listed as is, belongs-to, etc, between a Threat Actor SDO and Identity SDO, the STIX specification recommends to use attributed-to.

However, Relationship objects can be used to join any two STIX Objects, with any description of the relationship. The point is, common and object specific relationships should be observed where possible.

With this in mind, a Relationship object can also be used to join an SCO and an SDO.

For example, I might create an Indicator SDO (to detect Software vulnerable to a CVE) with a pattern (I’ll come onto those later) referencing a Software SCO as follows;

{

"type": "indicator",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "indicator--ecd38bb9-dfd2-4742-94ce-af790c0bcc4c",

"created_by_ref": "identity--d2916708-57b9-5636-8689-62f049e9f727",

"created": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"modified": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"name": "CVE-2030-00000",

"indicator_types": [

"compromised"

],

"pattern": "software:cpe='cpe:2.3:a:google:chrome:104.0.5112.43:*:*:*:*:*:*:*'",

"pattern_type": "stix",

"pattern_version": "2.1"

}

And the Software SCO with the same CPE as found in the pattern

{

"type": "software",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "software--0000ed91-7943-54fd-9b39-59a4309c0a9b",

"name": "Google Chrome 104.0.5112.43",

"cpe": "cpe:2.3:a:google:chrome:104.0.5112.43:*:*:*:*:*:*:*",

"vendor": "google",

"version": "104.0.5112.43"

}

I might then link these by saying the Software SCO (Google Chrome) is-vulnerable to the Indicator SDO (note, this is a non-standard relationship and description) as follows.

{

"type": "relationship",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "relationship--b87d9e0c-cda6-40eb-8fce-5cbace754b93",

"created": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"modified": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"relationship_type": "is-vulnerable",

"source_ref": "software--0000ed91-7943-54fd-9b39-59a4309c0a9b",

"target_ref": "indicator--ecd38bb9-dfd2-4742-94ce-af790c0bcc4c"

}

Relationship SRO or Embedded Relationships?

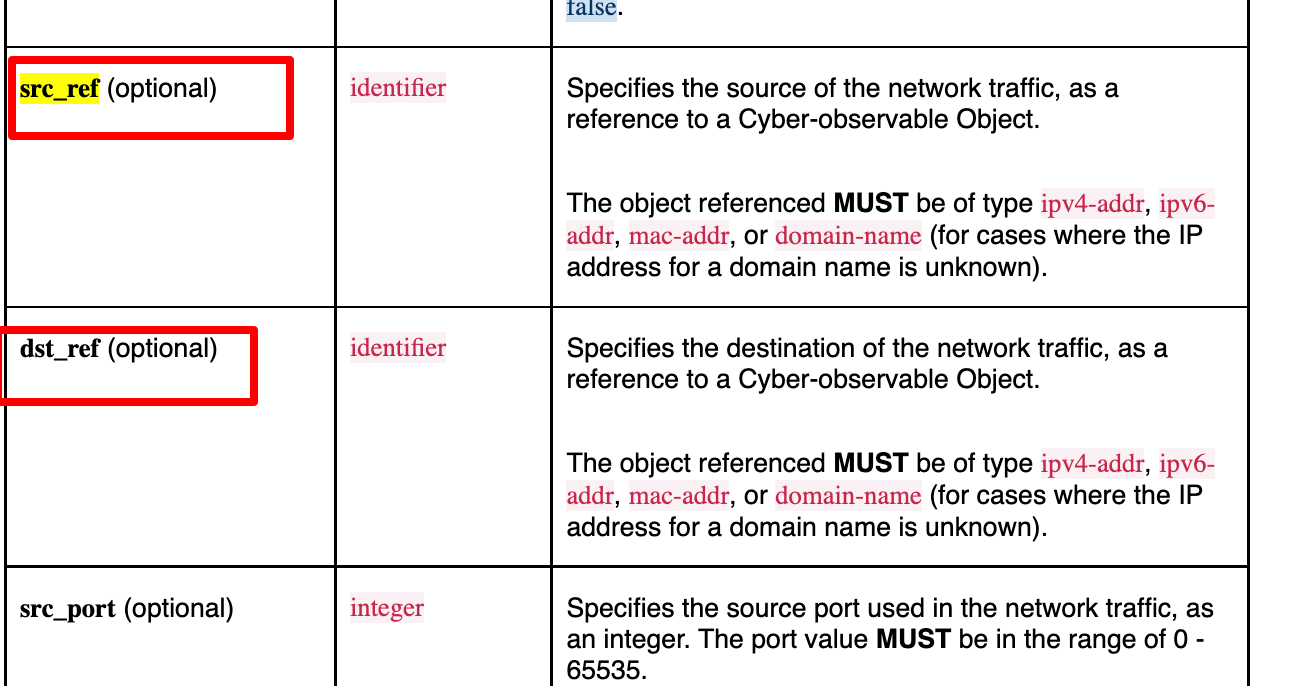

Earlier in this post I showed how SCOs and SDOs, and SCOs and SCOs can be linked using embedded properties like dst_ref, src_ref, and object_refs.

It is important to understand the right time to use embedded properties and when to use SROs.

Object Properties are predefined for an Object where such connection are fixed.

For example, a network request almost always has a Source IP (src_ref) and Destination IP (dst_ref), so it makes sense to include these in the Network Traffic SCOs specification.

However, often such relationships are not as prescriptive (and therefore nothing suitable exists in the specification of the Object to use).

A good example is a Malware’s C2 infrastructure.

The Infrastructure SDO does not have any predefined embedded relationship properties.

In other cases the Properties of an SDO might not suit your needs. The Malware SDO properties operating_system_refs and sample_refs can be used to link SCOs, but neither suits the needs to show the C2 IP addresses used by the Malware.

Instead of creating custom properties to handle such cases (more on custom properties in a future post), it is better to use SROs to describe the relationship between SDO and SRO.

Sighting SROs

Sightings are a concept in STIX designed to denote something has been seen.

For example, a threat intel team might author a report talking about a Threat Actor (SDO) using Malware (SDO) which uses an Infrastructure (SDO) which resolves to an IPv4 address (SCO).

At this point the work is forward looking research. However, the reality is that this Threat Actor might attempt to attack an environment I own.

The Sighting SRO contains extra properties not present on the generic Relationship SRO to do this. Sighting SROs define three unique aspects of a sighting relationship:

- What was sighted, such as the Indicator, Malware, Campaign, or other SDO (

sighting_of_ref) - Who sighted it and/or where it was sighted, represented as an Identity (

where_sighted_refs) - What was actually seen on systems and networks, represented as Observed Data (

observed_data_refs) - The times it was sighted (

first_seenandlast_seen)

The simplest example of a Sighting could be;

{

"type": "sighting",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "sighting--093e37e2-c7ec-4d63-aa0a-ee607477c2a1",

"created": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"modified": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"sighting_of_ref": "threat-actor--d64059ca-60b6-452e-8a53-7fa73a696ac7"

}

Here you can see the SDO being sighted in the sighting_of_ref embedded property. This must reference an SDO, and not an SCO.

Not being able to reference an SDO directly creates an issue. A Sighting (SRO) of a Threat Actor (SDO) with such little information does not explain to those looking at the STIX graph the evidence that the analyst saw to confirm the Threat Actor was Sighted.

That’s where the Observed Data (SDO) comes in.

Here’s how it can be used;

{

"type": "sighting",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "sighting--093e37e2-c7ec-4d63-aa0a-ee607477c2a1",

"created": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"modified": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"first_seen": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"last_seen": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"count": 1,

"sighting_of_ref": "threat-actor--d64059ca-60b6-452e-8a53-7fa73a696ac7",

"observed_data_refs": [

"observed-data--b67d30ff-02ac-498a-92f9-32f845f448cf"

],

"where_sighted_refs": [

"identity--d3f9a82b-7272-417e-9195-f3b0f68159e9"

]

}

The Observed Data SDO could then in turn point to a File SCO (which is perhaps also linked to a Malware the Threat Actor is known to use);

{

"type": "observed-data",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "observed-data--b67d30ff-02ac-498a-92f9-32f845f448cf",

"created": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"modified": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"first_observed": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"last_observed": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"number_observed": 1,

"object_refs": [

"file--30038539-3eb6-44bc-a59e-d0d3fe84695a"

]

}

In the original Sighting there is also a where_sighted_refs property where a list of Identity SDOs can be passed. This might be an Identity SDO for a SIEM tool where a detection rule has detected the file.

{

"type": "identity",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "identity--d3f9a82b-7272-417e-9195-f3b0f68159e9",

"created": "2016-04-06T20:03:00.000Z",

"modified": "2016-04-06T20:03:00.000Z",

"name": "Splunk Enterprise Security",

"identity_class": "system"

}

STIX Bundle Objects (SBOs)

Throughout this post I’ve been showing you objects with some relationships.

A STIX Bundle (SBO) is a type of object that provides a wrapper for packaging a complete set of STIX content together (“the story”).

The Properties of a STIX Bundle are simple. A Bundle has the Properties; type, id, and a list of STIX objects it contains (SDOs, SCOs, SROs, SMOs, etc.).

Here’s a bundle of object from the previous sighting example;

{

"type": "bundle",

"id": "bundle--44af6c39-c09b-49c5-9de2-394224b04982",

"objects": [

{

"type": "identity",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "identity--d3f9a82b-7272-417e-9195-f3b0f68159e9",

"created": "2016-04-06T20:03:00.000Z",

"modified": "2016-04-06T20:03:00.000Z",

"name": "Splunk Enterprise Security",

"identity_class": "system"

},

{

"type": "observed-data",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "observed-data--b67d30ff-02ac-498a-92f9-32f845f448cf",

"created": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"modified": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"first_observed": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"last_observed": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"number_observed": 1,

"object_refs": [

"file--30038539-3eb6-44bc-a59e-d0d3fe84695a"

]

},

{

"type": "sighting",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "sighting--093e37e2-c7ec-4d63-aa0a-ee607477c2a1",

"created": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"modified": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"first_seen": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"last_seen": "2020-01-06T00:00:00.000Z",

"count": 1,

"sighting_of_ref": "threat-actor--d64059ca-60b6-452e-8a53-7fa73a696ac7",

"observed_data_refs": ["observed-data--b67d30ff-02ac-498a-92f9-32f845f448cf"],

"where_sighted_refs": ["identity--d3f9a82b-7272-417e-9195-f3b0f68159e9"]

}

]

}

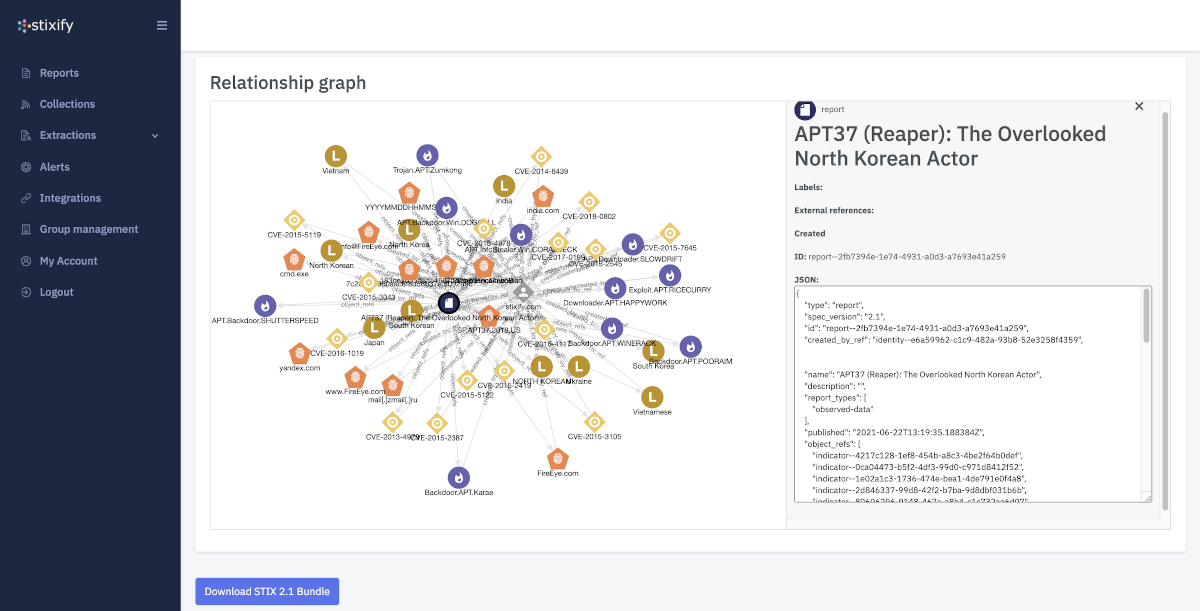

Bundles are useful mechanisms for packaging your STIX content for sharing to other people and tools (many of which can understand STIX bundles natively).

For example, our viewer below takes a STIX bundle URL and renders it. Here’s the above bundle in said viewer…

Try creating your own STIX objects (the easy way)

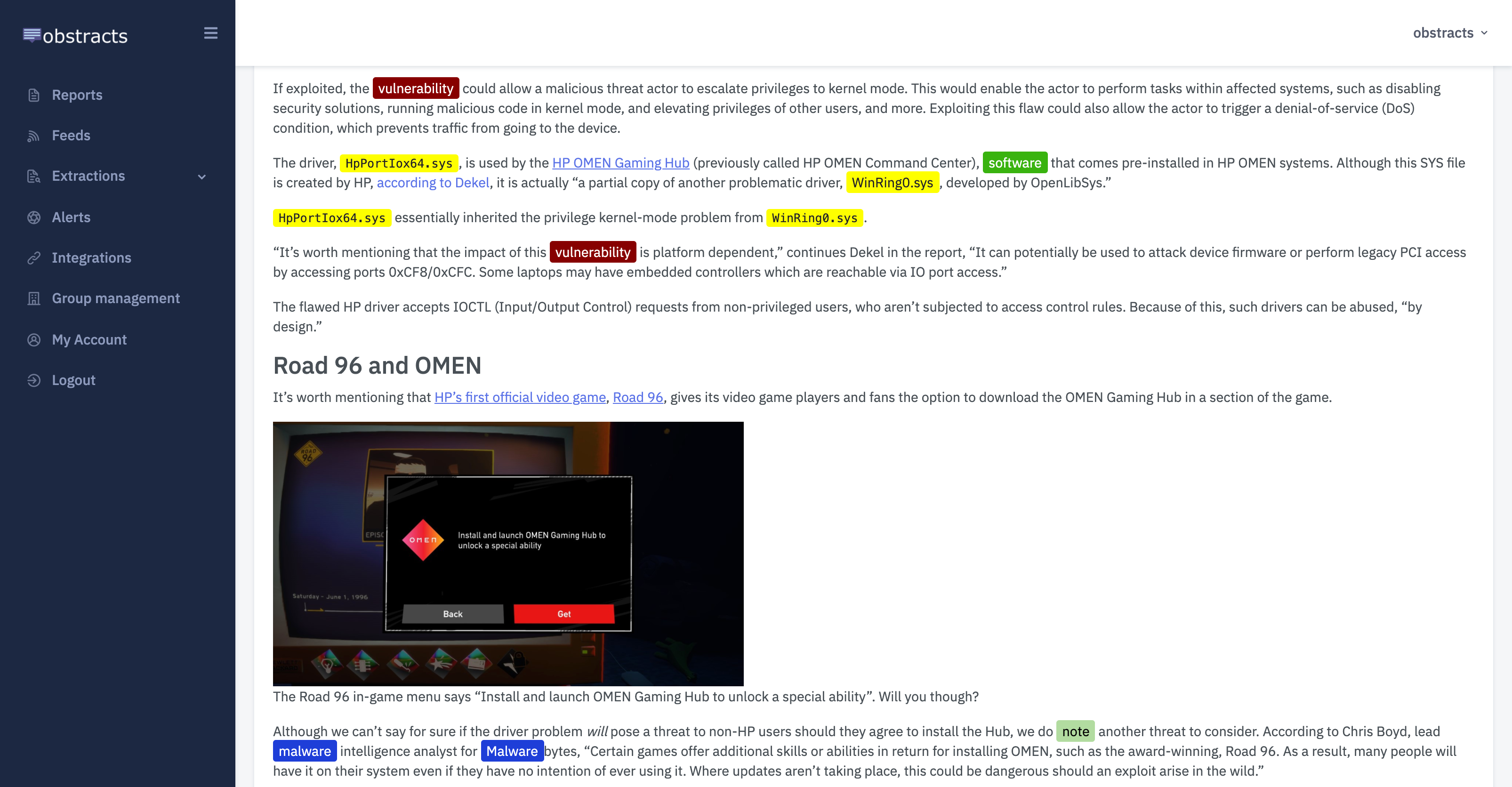

It is sometimes easier to jump straight in, and this would be one of those times. Generate your own STIX objects using from an existing intelligence report using txt2stix, then take a look at the types of objects generated and their relationships in graph structure to get a better feel as to what you can do with STIX.

Obstracts

The RSS reader for threat intelligence teams. Turn any blog into machine readable STIX 2.1 data ready for use with your security stack.

Stixify

Your automated threat intelligence analyst. Extract machine readable STIX 2.1 data ready for use with your security stack.

Discuss this post

Head on over to the dogesec community to discuss this post.

Never miss an update

Sign up to receive new articles in your inbox as they published.