If you are reading this blog post via a 3rd party source it is very likely that many parts of it will not render correctly. Please view the post on dogesec.com for the full interactive viewing experience.

If you prefer, you can also access the markdown of this post here.

tl;dr

RSS and ATOM feeds are problematic for two reasons; 1) lack of history, 2) contain limited post content. We built some software to fix that.

But why?

There are many brilliant cyber-security researchers sharing their findings via online blogs. If you are one of these people, thank you!

Much of the research they share publicly is incredibly comprehensive.

As such, for the last four years now I have been curating a list of awesome blogs that publish cyber threat intelligence research.

It currently lists over 300 feeds, with almost 200 stars!

However, most of the RSS and ATOM feeds listed in that repository, and more generally any blogs RSS and ATOM feeds, are limited in two ways;

- the feeds show the partial content of the article, requiring you to navigate to the blog post on the internet to read the entire article.

- the feeds contain a limited history of posts, typically about 20 posts (but this is determined by the blog owner).

Unless you have subscribed to a blog since its inception, there is no easy way to get a complete history of posts in that blog without having to web scrape.

For me, and perhaps you, this is problematic because there is no easy way to access historic research.

If you are wondering why I would want to do this, let me explain with a simple example…

A few months ago I was researching CVE-2024-3094, as was every-single security researcher on the planet.

Which brings me to problem 1;

Problem 1: Partial Feed Content

When it comes to working with RSS and ATOM feeds, I like to have a local copy of the post for text search.

By being able to search and pivot on my machine in this way I can easily drill down on particular parts of the research being described in different ways, by different authors.

In the case of CVE-2024-3094, this could be a search for build-to-host.m4 to read how authors of each post I have indexed describe what is unpacked by this macro, and ultimately what the unpacked content does.

Problem is; almost all RSS feeds only contain a summary of the articles actual content, not the full article.

Take this example from PANs Unit42 ATOM feed:

<item>

<title>Threat Brief: Vulnerability in XZ Utils Data Compression Library Impacting Multiple Linux Distributions (CVE-2024-3094)</title>

<link>https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/threat-brief-xz-utils-cve-2024-3094/</link>

<guid isPermaLink="false">https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/?p=133225</guid>

<description>

<![CDATA[ <p>An overview of CVE-2024-3094, a vulnerability in XZ Utils, and information about how to mitigate.</p> <p>The post <a href="https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/threat-brief-xz-utils-cve-2024-3094/">Threat Brief: Vulnerability in XZ Utils Data Compression Library Impacting Multiple Linux Distributions (CVE-2024-3094)</a> appeared first on <a href="https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com">Unit 42</a>.</p> ]]>

</description>

</item>

The <description> property contains a paragraph of data. Compare that to the full post content by visiting the <link> (https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/threat-brief-xz-utils-cve-2024-3094/), which contains paragraphs, images, tables, etc.

If you look at the HTML code for the article, you will also see the content is wrapped up in unrelated (e.g. nav bar) and other messy (e.g. CSS) HTML content.

Step in readability-lxml, a Python library that takes a html document, pulls out the main body of text (for blogs, the post), and cleans it up.

Thus, to get the full text needed I can;

- take the

<link>value - grab the HTML content (e.g.

curl -L -o code.html http://website.domain) - run it through readability-lxml to get the post content (the

doc.summary())

Problem solved.

Which brings me nicely on to problem 2…

Problem 2: Limited history in feeds

CVE-2024-3094 is relatively new. It has only existed for a few months.

However, in many cases malicious actors rehash old tactics, techniques and procedures.

Searching through historic data based on information about current threats can uncover similarities with past research, and thus aid the running investigation.

Though as mentioned earlier, most blogs tend to limit the blog items posted in their feeds. I’ve found no more than the 20 most recent posts exist in a feed, at best.

Thinking for an hour-or-two I came to the conclusion there are two feasible approaches to getting content for posts that are no longer found in feeds provided for the blog;

- Scrape the blog for historic posts. Probably the most accurate way to do it, though given the different structure of blogs and websites, this can become complex, requiring a fair bit of manual scraping logic to be written for each blog you want to follow. I’m sure an AI model could also be useful for this too, but this would likely require some fine-tuning for each blog. Or;

- Use the Wayback Machine’s archive. In the case of popular blogs the Wayback Machine will likely have captured many snapshots of a feed (though not always). For example, the feed for The Record by Recorded Future (

https://therecord.media/feed/) has, at the time of writing, been captured 187 times between 260 times between November 1, 2020 and December 7, 2023.

Here is one such snapshot taken by the Wayback Machine on July 8th 2023: https://web.archive.org/web/20230708200712/https://therecord.media/feed

Step in waybackpack, a command-line tool that lets you download the entire Wayback Machine archive for a given URL.

In the following command I am requesting all unique feed pages downloaded by the Wayback Machine (--uniques-only) from 2020 (--from-date 2020) from the feed URL https://therecord.media/feed/ with each item to be written to a directory called therecord_media_feed.

Try it out…

waybackpack https://therecord.media/feed/ -d therecord_media_feed --from-date 2020 --uniques-only

This run produces 100’s of unique index.html files (where index.html is the actual RSS feed in pure XML). Each index.html is nested in directories named with the index datetime (time captured by Wayback Machine) in the format YYYYMMDDHHMMSS like so;

therecord_media_feed

├── 20220808162900

│ └── therecord.media

│ └── feed

│ └── index.html

├── 20220805213430

│ └── therecord.media

│ └── feed

│ └── index.html

...

└── 20201101220102

└── therecord.media

└── feed

└── index.html

It is important to point out unique entries (defined in the CLI) just means the index.html files have at least one difference. That is to say, much of the file can actually be the same (thus in this case, include the same feed items).

Take 20220808162900 > therecord.media > index.html and 20220805213430 > therecord.media > index.html

Both of these files contain the item;

<item>

<title>Twitter confirms January breach, urges pseudonymous accounts to not add email or phone number</title>

<link>https://therecord.media/twitter-confirms-january-breach-urges-pseudonymous-accounts-to-not-add-email-or-phone-number/</link>

Therefore, the final step of the process requires de-duplication of feed items. This process can be done using the <link> values, first by searching for duplicates and then selecting the most recent feed entry (by Wayback Machine capture time) for the entry to be stored.

Again, problem 1 persists (partial post content) exists with this approach, but I have already shown you how to deal with that.

Putting it into action with history4feed

history4feed, creates a complete full text historical archive for an RSS or ATOM feed using the logic described above.

Once you’ve installed history4feed and started using the instructions linked above, you can start adding RSS and ATOM feeds.

Two tips before you get started

- our Awesome Threat Intel Blogs repository contains hundreds of feeds from blogs writing about cyber threat intelligence.

- if you’re more comfortable using a web interface you can use the Swagger UI (http://127.0.0.1:8000/schema/swagger-ui/) to interact with the API.

Adding a new blog

I’ll use the Ransomware feed from Brian Kreb’s brilliant blog;

https://krebsonsecurity.com/category/ransomware/feed/

Adding this to history4feed;

curl -X 'POST' \

'http://127.0.0.1:8000/api/v1/feeds/' \

-H 'accept: application/json' \

-H 'Content-Type: application/json' \

-d '{

"url": "https://krebsonsecurity.com/category/ransomware/feed/",

"retrieve_full_text": true

}'

{

"description": "In-depth security news and investigation",

"title": "Ransomware – Krebs on Security",

"feed_type": "rss",

"url": "https://krebsonsecurity.com/category/ransomware/feed/",

"job_state": "pending",

"id": "63794870-c001-4927-990c-04645bf3905c",

"job_id": "90bfb933-7062-4e1f-b6c4-85bb20159e9a"

}

Getting the status of an import

You’ll see the response contains a Job ID. Jobs are what are responsible for getting the historic posts and grabbing the full text of the blog.

I can monitor the state of this job as follows;

curl -X 'GET' \

'http://127.0.0.1:8000/api/v1/jobs/90bfb933-7062-4e1f-b6c4-85bb20159e9a/' \

-H 'accept: application/json'

{

"id": "90bfb933-7062-4e1f-b6c4-85bb20159e9a",

"count_of_items": 72,

"feed_id": "63794870-c001-4927-990c-04645bf3905c",

"state": "success",

"run_datetime": "2024-06-13T07:14:52.155528Z",

"earliest_item_requested": "2020-01-01T00:00:00Z",

"latest_item_requested": "2024-06-13T07:14:52.154931Z",

"info": ""

}

You can see 72 items (count_of_items) were processed from this blog between 2020-01-01 (earliest_item_requested) and 2024-06-13 (latest_item_requested). history 4 feed will always request the latest blog posts. The earliest_item_requested, that is the earliest item collected from the blog by history4feed, is defined in the history4feed configoration.

Browse Posts

The posts can now be searched and viewed;

curl -X 'GET' \

'http://127.0.0.1:8000/api/v1/feeds/63794870-c001-4927-990c-04645bf3905c/posts/' \

-H 'accept: application/json'

{

"page_size": 100,

"page_number": 1,

"page_results_count": 72,

"total_results_count": 72,

"posts": [

{

"id": "4ada9e26-6052-44ae-95d2-27751bcf0bf3",

"datetime_added": "2024-06-13T07:16:29.568860Z",

"datetime_updated": "2024-06-13T07:16:29.568867Z",

"title": "‘Operation Endgame’ Hits Malware Delivery Platforms",

"description": "<html><body><div><div class=\"entry-content\">\r\n\t\t\t\t\t\t\t\t\t\t\t\t<p>Law enforcement agencies in the United States and Europe today announced <strong>Operation Endgame</strong>, a coordinated action against some of the most popular cybercrime platforms for delivering ransomware and data-stealing malware. Dubbed “the largest ever operation against botnets,” the international effort is being billed as the opening salvo in an ongoing campaign targeting advanced malware “droppers” or “loaders” like <strong>IcedID</strong>, <strong>Smokeloader</strong> and <strong>Trickbot</strong>.</p>\n<div id=\"attachment_67699\" class=\"wp-caption aligncenter\"><img aria-describedby=\"caption-attachment-67699\" decoding=\"async\" class=\" wp-image-67699\" src=\"https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/endgamestill.png\" alt=\"\" srcset=\"https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/endgamestill.png 998w, https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/endgamestill-768x696.png 768w, https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/endgamestill-782x708.png 782w\" sizes=\"(max-width: 749px) 100vw, 749px\"><p id=\"caption-attachment-67699\" class=\"wp-caption-text\">A frame from one of three animated videos released today in connection with Operation Endgame.</p></div>\n<p>Operation Endgame targets the cybercrime ecosystem supporting droppers/loaders, slang terms used to describe tiny, custom-made programs designed to surreptitiously install malware onto a target system. Droppers are typically used in the initial stages of a breach, and they allow cybercriminals to bypass security measures and deploy additional harmful programs, including viruses, ransomware, or spyware.</p>\n<p>Droppers like IcedID are most often deployed through email attachments, hacked websites, or bundled with legitimate software. For example, cybercriminals have long used <a href=\"https://krebsonsecurity.com/2024/01/using-google-search-to-find-software-can-be-risky/\" target=\"_blank\" rel=\"noopener\">paid ads on Google to trick people into installing malware</a> disguised as popular free software, such as Microsoft Teams, Adobe Reader and Discord. In those cases, the dropper is the hidden component bundled with the legitimate software that quietly loads malware onto the user’s system.</p>\n<p>Droppers remain such a critical, human-intensive component of nearly all major cybercrime enterprises that the most popular have turned into full-fledged cybercrime services of their own. By targeting the individuals who develop and maintain dropper services and their supporting infrastructure, authorities are hoping to disrupt multiple cybercriminal operations simultaneously.</p>\n<p>According to <a href=\"https://www.europol.europa.eu/media-press/newsroom/news/largest-ever-operation-against-botnets-hits-dropper-malware-ecosystem\" target=\"_blank\" rel=\"noopener\">a statement</a> from the European police agency <strong>Europol</strong>, between May 27 and May 29, 2024 authorities arrested four suspects (one in Armenia and three in Ukraine), and disrupted or took down more than 100 Internet servers in Bulgaria, Canada, Germany, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Romania, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, United States and Ukraine. Authorities say they also seized more than 2,000 domain names that supported dropper infrastructure online.</p>\n<p>In addition, Europol released information on eight fugitives suspected of involvement in dropper services and who are wanted by Germany; their names and photos were added to Europol’s “Most Wanted” list on 30 May 2024.<span id=\"more-67691\"></span></p>\n<div id=\"attachment_67696\" class=\"wp-caption aligncenter\"><a href=\"https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/europol-mostwanted-de.png\" target=\"_blank\" rel=\"noopener\"><img aria-describedby=\"caption-attachment-67696\" decoding=\"async\" loading=\"lazy\" class=\"wp-image-67696\" src=\"https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/europol-mostwanted-de.png\" alt=\"\" srcset=\"https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/europol-mostwanted-de.png 1307w, https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/europol-mostwanted-de-768x337.png 768w, https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/europol-mostwanted-de-782x343.png 782w\" sizes=\"(max-width: 748px) 100vw, 748px\"></a><p id=\"caption-attachment-67696\" class=\"wp-caption-text\">A “wanted” poster including the names and photos of eight suspects wanted by Germany and now on Europol’s “Most Wanted” list.</p></div>\n<p>“It has been discovered through the investigations so far that one of the main suspects has earned at least EUR 69 million in cryptocurrency by renting out criminal infrastructure sites to deploy ransomware,” Europol wrote. “The suspect’s transactions are constantly being monitored and legal permission to seize these assets upon future actions has already been obtained.”</p>\n<p>There have been <a href=\"https://krebsonsecurity.com/2023/08/u-s-hacks-qakbot-quietly-removes-botnet-infections/\" target=\"_blank\" rel=\"noopener\">numerous such coordinated malware takedown efforts</a> in the past, and yet often the substantial amount of coordination required between law enforcement agencies and cybersecurity firms involved is not sustained after the initial disruption and/or arrests.</p>\n<p>But a new website erected to detail today’s action — <a href=\"https://www.operation-endgame.com\" target=\"_blank\" rel=\"noopener\">operation-endgame.com</a> — makes the case that this time is different, and that more takedowns and arrests are coming. “Operation Endgame does not end today,” the site promises. “New actions will be announced on this website.”</p>\n<div id=\"attachment_67697\" class=\"wp-caption aligncenter\"><img aria-describedby=\"caption-attachment-67697\" decoding=\"async\" loading=\"lazy\" class=\"size-full wp-image-67697\" src=\"https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/endgame-think.png\" alt=\"\"><p id=\"caption-attachment-67697\" class=\"wp-caption-text\">A message on operation-endgame.com promises more law enforcement and disruption actions.</p></div>\n<p>Perhaps in recognition that many of today’s top cybercriminals reside in countries that are effectively beyond the reach of international law enforcement, actions like Operation Endgame seem increasingly focused on mind games — i.e., trolling the hackers.</p>\n<p>Writing in this month’s issue of <em>Wired</em>, <strong>Matt Burgess</strong> makes the case that Western law enforcement officials have turned to psychological measures as an added way to slow down Russian hackers and cut to the heart of the sweeping cybercrime ecosystem.</p>\n<p>“These nascent psyops include efforts to erode the limited trust the criminals have in each other, driving subtle wedges between fragile hacker egos, and sending offenders personalized messages showing they’re being watched,” Burgess <a href=\"https://www.wired.com/story/cop-cybercriminal-hacker-psyops/\" target=\"_blank\" rel=\"noopener\">wrote</a>.</p>\n<p>When authorities in the U.S. and U.K. announced in February 2024 that they’d <a href=\"https://krebsonsecurity.com/2024/02/feds-seize-lockbit-ransomware-websites-offer-decryption-tools-troll-affiliates/\" target=\"_blank\" rel=\"noopener\">infiltrated and seized</a> the infrastructure used by the infamous <strong>LockBit</strong> ransomware gang, they borrowed the existing design of LockBit’s victim shaming website to link instead to press releases about the takedown, and included a countdown timer that was eventually replaced with the personal details of <a href=\"https://krebsonsecurity.com/2024/05/how-did-authorities-identify-the-alleged-lockbit-boss/\" target=\"_blank\" rel=\"noopener\">LockBit’s alleged leader</a>.</p>\n<div id=\"attachment_66436\" class=\"wp-caption aligncenter\"><img aria-describedby=\"caption-attachment-66436\" decoding=\"async\" loading=\"lazy\" class=\" wp-image-66436\" src=\"https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/lockbitseized.png\" alt=\"\" srcset=\"https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/lockbitseized.png 1379w, https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/lockbitseized-768x486.png 768w, https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/lockbitseized-782x494.png 782w\" sizes=\"(max-width: 750px) 100vw, 750px\"><p id=\"caption-attachment-66436\" class=\"wp-caption-text\">The feds used the existing design on LockBit’s victim shaming website to feature press releases and free decryption tools.</p></div>\n<p>The Operation Endgame website also includes a countdown timer, which serves to tease the release of several animated videos that mimic the same sort of flashy, short advertisements that established cybercriminals often produce to promote their services online. At least two of the videos include a substantial amount of text written in Russian.</p>\n<p>The coordinated takedown comes on the heels of another law enforcement action this week against what the director of the FBI called “<a href=\"https://krebsonsecurity.com/2024/05/is-your-computer-part-of-the-largest-botnet-ever/\" target=\"_blank\" rel=\"noopener\">likely the world’s largest botnet ever</a>.” On Wednesday <strong>U.S. Department of Justice</strong> (DOJ) announced the arrest of <strong>YunHe Wang</strong>, the alleged operator of the ten-year-old online anonymity service <strong>911 S5</strong>. The government also seized 911 S5’s domains and online infrastructure, which allegedly turned computers running various “free VPN” products into Internet traffic relays that facilitated billions of dollars in online fraud and cybercrime.</p>\n\t\t\t\t\t\t\t\t\t\t\t</div>\r\n\t\t\r\n\t\t\t\r\n\t\r\n\t</div></body></html>",

"link": "https://krebsonsecurity.com/2024/05/operation-endgame-hits-malware-delivery-platforms/",

"pubdate": "2024-05-30T15:19:44Z",

"author": "BrianKrebs",

"is_full_text": true,

"content_type": "text/html; charset=utf-8",

"categories": [

"ransomware",

"the-coming-storm",

"neer-do-well-news",

"trickbot",

"europol",

"lockbit",

"911-s5",

"icedid",

"matt-burgess",

"operation-endgame",

"smokeloader"

]

},

This endpoint also contains search filter (e.g. by title or description) to filter the results.

e.g.

curl -X 'GET' \

'http://127.0.0.1:8000/api/v1/feeds/63794870-c001-4927-990c-04645bf3905c/posts/?title=malware' \

-H 'accept: application/json'

{

"page_size": 100,

"page_number": 1,

"page_results_count": 1,

"total_results_count": 1,

"posts": [

{

"id": "4ada9e26-6052-44ae-95d2-27751bcf0bf3",

"datetime_added": "2024-06-13T07:16:29.568860Z",

"datetime_updated": "2024-06-13T07:16:29.568867Z",

"title": "‘Operation Endgame’ Hits Malware Delivery Platforms",

Use history4feed with a feed reader

Many people use feed readers that understand RSS or ATOM (not our custom JSON structure).

As such, history4feed, provides the option to return the blog posts as RSS structured XML;

curl -X 'GET' \

'http://127.0.0.1:8000/api/v1/feeds/63794870-c001-4927-990c-04645bf3905c/posts/xml/' \

-H 'accept: application/json'

<?xml version="1.0" ?>

<rss version="2.0">

<channel>

<title>Ransomware – Krebs on Security</title>

<description>In-depth security news and investigation</description>

<link>https://krebsonsecurity.com/category/ransomware/feed/</link>

<lastBuildDate>2024-05-30T15:19:44+00:00</lastBuildDate>

<item>

<title>‘Operation Endgame’ Hits Malware Delivery Platforms</title>

<link href="https://krebsonsecurity.com/2024/05/operation-endgame-hits-malware-delivery-platforms/">https://krebsonsecurity.com/2024/05/operation-endgame-hits-malware-delivery-platforms/</link>

<pubDate>2024-05-30T15:19:44+00:00</pubDate>

<description><html><body><div><div class="entry-content">

<p>Law enforcement agencies in the United States and Europe today announced <strong>Operation Endgame</strong>, a coordinated action against some of the most popular cybercrime platforms for delivering ransomware and data-stealing malware. Dubbed “the largest ever operation against botnets,” the international effort is being billed as the opening salvo in an ongoing campaign targeting advanced malware “droppers” or “loaders” like <strong>IcedID</strong>, <strong>Smokeloader</strong> and <strong>Trickbot</strong>.</p>

<div id="attachment_67699" class="wp-caption aligncenter"><img aria-describedby="caption-attachment-67699" decoding="async" class=" wp-image-67699" src="https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/endgamestill.png" alt="" srcset="https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/endgamestill.png 998w, https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/endgamestill-768x696.png 768w, https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/endgamestill-782x708.png 782w" sizes="(max-width: 749px) 100vw, 749px"><p id="caption-attachment-67699" class="wp-caption-text">A frame from one of three animated videos released today in connection with Operation Endgame.</p></div>

<p>Operation Endgame targets the cybercrime ecosystem supporting droppers/loaders, slang terms used to describe tiny, custom-made programs designed to surreptitiously install malware onto a target system. Droppers are typically used in the initial stages of a breach, and they allow cybercriminals to bypass security measures and deploy additional harmful programs, including viruses, ransomware, or spyware.</p>

<p>Droppers like IcedID are most often deployed through email attachments, hacked websites, or bundled with legitimate software. For example, cybercriminals have long used <a href="https://krebsonsecurity.com/2024/01/using-google-search-to-find-software-can-be-risky/" target="_blank" rel="noopener">paid ads on Google to trick people into installing malware</a> disguised as popular free software, such as Microsoft Teams, Adobe Reader and Discord. In those cases, the dropper is the hidden component bundled with the legitimate software that quietly loads malware onto the user’s system.</p>

<p>Droppers remain such a critical, human-intensive component of nearly all major cybercrime enterprises that the most popular have turned into full-fledged cybercrime services of their own. By targeting the individuals who develop and maintain dropper services and their supporting infrastructure, authorities are hoping to disrupt multiple cybercriminal operations simultaneously.</p>

<p>According to <a href="https://www.europol.europa.eu/media-press/newsroom/news/largest-ever-operation-against-botnets-hits-dropper-malware-ecosystem" target="_blank" rel="noopener">a statement</a> from the European police agency <strong>Europol</strong>, between May 27 and May 29, 2024 authorities arrested four suspects (one in Armenia and three in Ukraine), and disrupted or took down more than 100 Internet servers in Bulgaria, Canada, Germany, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Romania, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, United States and Ukraine. Authorities say they also seized more than 2,000 domain names that supported dropper infrastructure online.</p>

<p>In addition, Europol released information on eight fugitives suspected of involvement in dropper services and who are wanted by Germany; their names and photos were added to Europol’s “Most Wanted” list on 30 May 2024.<span id="more-67691"></span></p>

<div id="attachment_67696" class="wp-caption aligncenter"><a href="https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/europol-mostwanted-de.png" target="_blank" rel="noopener"><img aria-describedby="caption-attachment-67696" decoding="async" loading="lazy" class="wp-image-67696" src="https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/europol-mostwanted-de.png" alt="" srcset="https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/europol-mostwanted-de.png 1307w, https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/europol-mostwanted-de-768x337.png 768w, https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/europol-mostwanted-de-782x343.png 782w" sizes="(max-width: 748px) 100vw, 748px"></a><p id="caption-attachment-67696" class="wp-caption-text">A “wanted” poster including the names and photos of eight suspects wanted by Germany and now on Europol’s “Most Wanted” list.</p></div>

<p>“It has been discovered through the investigations so far that one of the main suspects has earned at least EUR 69 million in cryptocurrency by renting out criminal infrastructure sites to deploy ransomware,” Europol wrote. “The suspect’s transactions are constantly being monitored and legal permission to seize these assets upon future actions has already been obtained.”</p>

<p>There have been <a href="https://krebsonsecurity.com/2023/08/u-s-hacks-qakbot-quietly-removes-botnet-infections/" target="_blank" rel="noopener">numerous such coordinated malware takedown efforts</a> in the past, and yet often the substantial amount of coordination required between law enforcement agencies and cybersecurity firms involved is not sustained after the initial disruption and/or arrests.</p>

<p>But a new website erected to detail today’s action — <a href="https://www.operation-endgame.com" target="_blank" rel="noopener">operation-endgame.com</a> — makes the case that this time is different, and that more takedowns and arrests are coming. “Operation Endgame does not end today,” the site promises. “New actions will be announced on this website.”</p>

<div id="attachment_67697" class="wp-caption aligncenter"><img aria-describedby="caption-attachment-67697" decoding="async" loading="lazy" class="size-full wp-image-67697" src="https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/endgame-think.png" alt=""><p id="caption-attachment-67697" class="wp-caption-text">A message on operation-endgame.com promises more law enforcement and disruption actions.</p></div>

<p>Perhaps in recognition that many of today’s top cybercriminals reside in countries that are effectively beyond the reach of international law enforcement, actions like Operation Endgame seem increasingly focused on mind games — i.e., trolling the hackers.</p>

<p>Writing in this month’s issue of <em>Wired</em>, <strong>Matt Burgess</strong> makes the case that Western law enforcement officials have turned to psychological measures as an added way to slow down Russian hackers and cut to the heart of the sweeping cybercrime ecosystem.</p>

<p>“These nascent psyops include efforts to erode the limited trust the criminals have in each other, driving subtle wedges between fragile hacker egos, and sending offenders personalized messages showing they’re being watched,” Burgess <a href="https://www.wired.com/story/cop-cybercriminal-hacker-psyops/" target="_blank" rel="noopener">wrote</a>.</p>

<p>When authorities in the U.S. and U.K. announced in February 2024 that they’d <a href="https://krebsonsecurity.com/2024/02/feds-seize-lockbit-ransomware-websites-offer-decryption-tools-troll-affiliates/" target="_blank" rel="noopener">infiltrated and seized</a> the infrastructure used by the infamous <strong>LockBit</strong> ransomware gang, they borrowed the existing design of LockBit’s victim shaming website to link instead to press releases about the takedown, and included a countdown timer that was eventually replaced with the personal details of <a href="https://krebsonsecurity.com/2024/05/how-did-authorities-identify-the-alleged-lockbit-boss/" target="_blank" rel="noopener">LockBit’s alleged leader</a>.</p>

<div id="attachment_66436" class="wp-caption aligncenter"><img aria-describedby="caption-attachment-66436" decoding="async" loading="lazy" class=" wp-image-66436" src="https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/lockbitseized.png" alt="" srcset="https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/lockbitseized.png 1379w, https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/lockbitseized-768x486.png 768w, https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/lockbitseized-782x494.png 782w" sizes="(max-width: 750px) 100vw, 750px"><p id="caption-attachment-66436" class="wp-caption-text">The feds used the existing design on LockBit’s victim shaming website to feature press releases and free decryption tools.</p></div>

<p>The Operation Endgame website also includes a countdown timer, which serves to tease the release of several animated videos that mimic the same sort of flashy, short advertisements that established cybercriminals often produce to promote their services online. At least two of the videos include a substantial amount of text written in Russian.</p>

<p>The coordinated takedown comes on the heels of another law enforcement action this week against what the director of the FBI called “<a href="https://krebsonsecurity.com/2024/05/is-your-computer-part-of-the-largest-botnet-ever/" target="_blank" rel="noopener">likely the world’s largest botnet ever</a>.” On Wednesday <strong>U.S. Department of Justice</strong> (DOJ) announced the arrest of <strong>YunHe Wang</strong>, the alleged operator of the ten-year-old online anonymity service <strong>911 S5</strong>. The government also seized 911 S5’s domains and online infrastructure, which allegedly turned computers running various “free VPN” products into Internet traffic relays that facilitated billions of dollars in online fraud and cybercrime.</p>

</div>

</div></body></html></description>

<category>ransomware</category>

<category>the-coming-storm</category>

<category>neer-do-well-news</category>

<category>trickbot</category>

<category>europol</category>

<category>lockbit</category>

<category>911-s5</category>

<category>icedid</category>

<category>matt-burgess</category>

<category>operation-endgame</category>

<category>smokeloader</category>

<author>

<name>BrianKrebs</name>

</author>

</item>

You can add this feed to your feed reader using the URL of the endpoint…

http://127.0.0.1:8000/api/v1/feeds/63794870-c001-4927-990c-04645bf3905c/posts/xml/

My research workflow

history4feed has plenty of options to filter and search posts across blogs that prove incredibly useful for researching specific topics.

You can go a step further and extract cyber threat intelligence from posts automatically as follows;

- Subscribe to a blog using history4feed

- Convert blog post in history4feed to markdown

- Put the markdown file into txt2stix which will extract intelligence from it as STIX objects

- Get a machine readable STIX 2.1 bundle to use with downstream security tools

p.s Obstracts will automate that workflow for you.

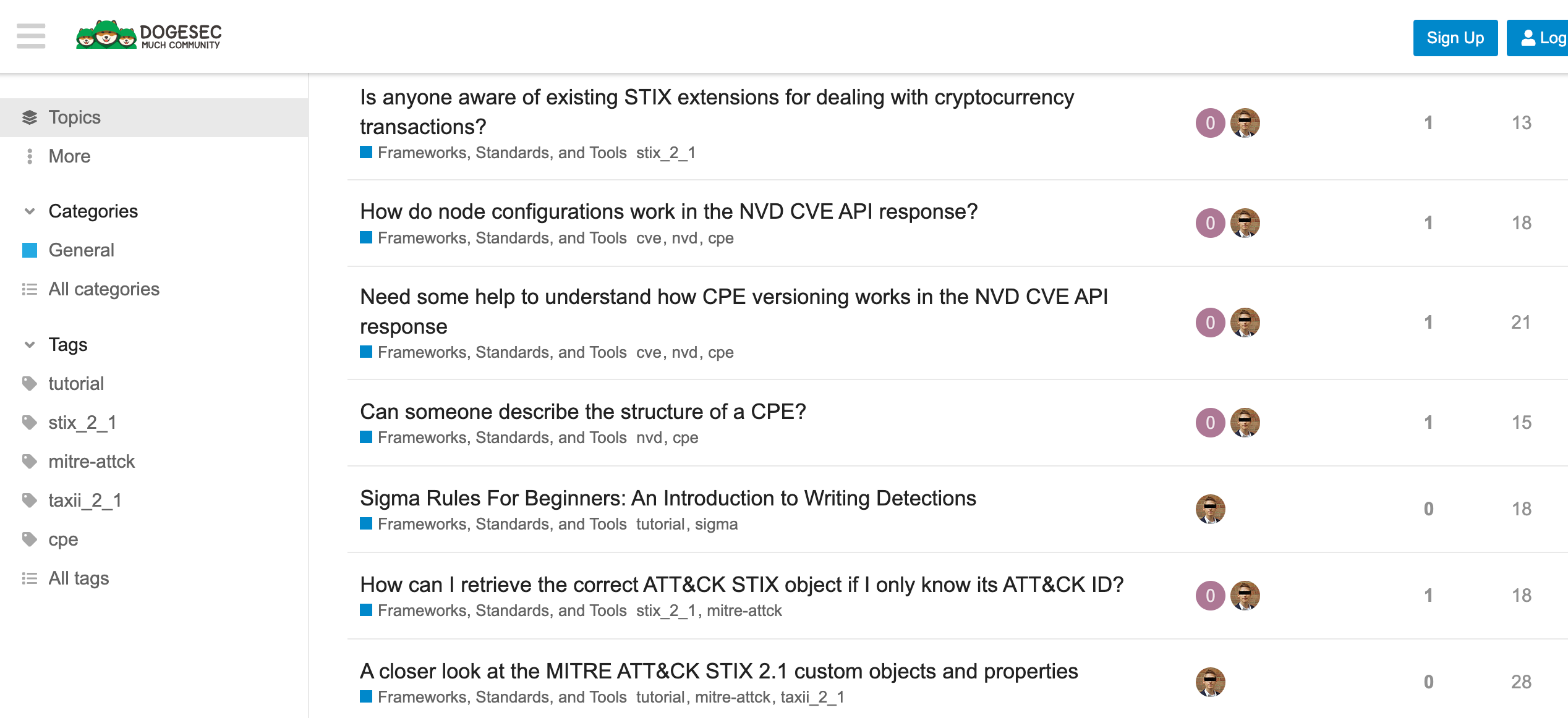

Discuss this post

Head on over to the DOGESEC community to discuss this post.

Never miss an update

Sign up to receive new articles in your inbox as they published.